More than 125 years after we started observing “labour day”, ominous headlines scream of jobs decreased dramatically by technology. Countless opinions and studies project how Artificial intelligence (AI) will take away jobs and reduce the affected humans to heaps of despair. AI-graduating-from-college-to-replace-workers dominates political debates.

Should technology-driven automation be our sole concern about reduced demand for labour and loss of jobs in the economy? Has automation not existed in our midst for thousands of years where it served to augment human labour, to help us evolve our higher competencies?

Is the correlation between job reduction and automation an open-and-shut case?

Jobsageddon

In the 21st century, the convergence of multiple factors beyond automation sets us up for an armageddon of jobs and associated societal change – a jobsageddon.

Those factors are:

- Borderless Labour

- Longevity, and

- Sharing Economy

Here’s a brief look at each and the threats they pose vis-a-vis the oft-repeated bugaboo of automation.

1. Borderless Labour – a.k.a Diaspora of Jobs

20th century saw the physical movement of people across countries – often the move was from undeveloped economies to developed economies. Depending on whether your country was on the sending or receiving side of this people movement, it was referred to as immigration, emigration, bain-drain etc.

Jobs are moving in the reverse direction, from the developed economies to the developing economies.

This job diaspora is a reverse osmosis of jobs homing in on skills causing a job diaspora.

This goes beyond the smart-sourcing in manufacturing or business process outsourcing (BPO) where call center work or paralegal work migrated to Asia from US and Europe.

The effectiveness and lower cost of communications and collaboration technologies, coupled with job brokering platforms like Upwork has made it much easier to source labor from outside national boundaries.

Why would we hire a graphics designer in New York when we can find one in Bangladesh for a fraction of the hourly rate in New York?

Assuming job performance is assured, we would not, unless motivated by some variation of the be-local-buy-local fervor.

Until now, simplistic protectionism has been focused on raising the cost of imported goods – and indirectly the cost of farm and manufacturing labour – not on stopping the outward leakage of service-sector jobs.

National boundaries, effective at stopping the flow of goods and people, are currently porous when it comes to labour. Even language barriers that kept jobs within nations are being eroded by technolgy-assisted translation.

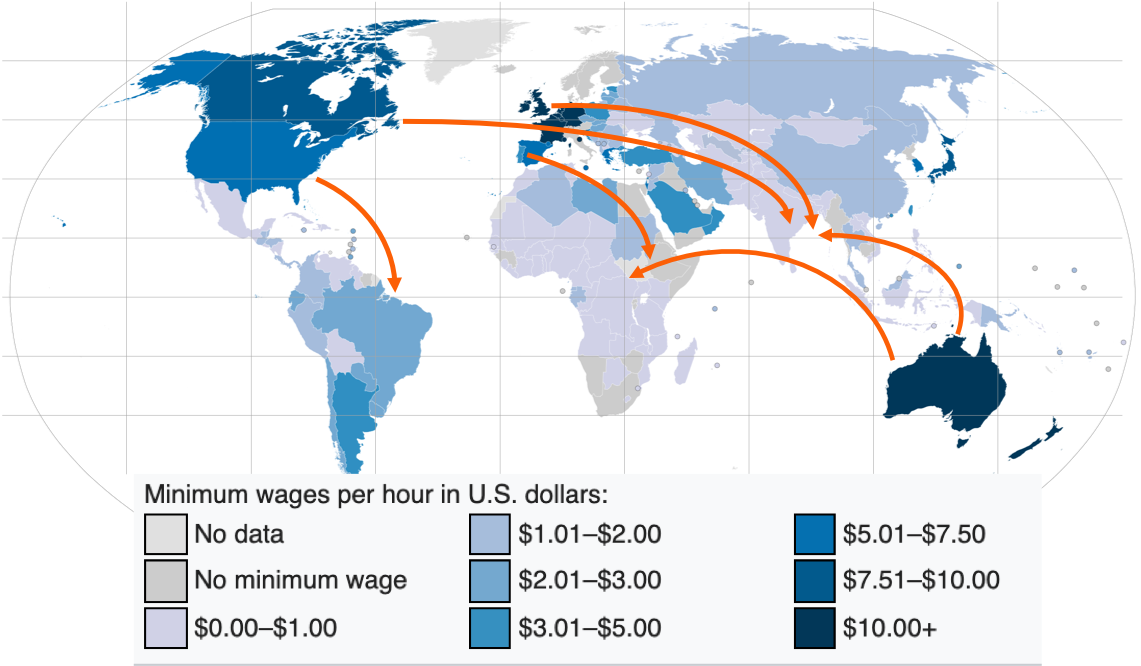

The graphic below shows the potential for labor-arbitrage, given the wage rates in different countries.

This osmosis of labour flow is a supply shock to labor markets in developed countries.

How will global on-demand-labor affect the society in developed economies? Are we headed to social unrest in the west?

2. Longevity

Not only did the 20th century saw movement of people and jobs, it also saw advances in medicine that dramatically reduced infectious diseases and infant mortality. The result is not simply an increase in older population, but an increase in labour force.

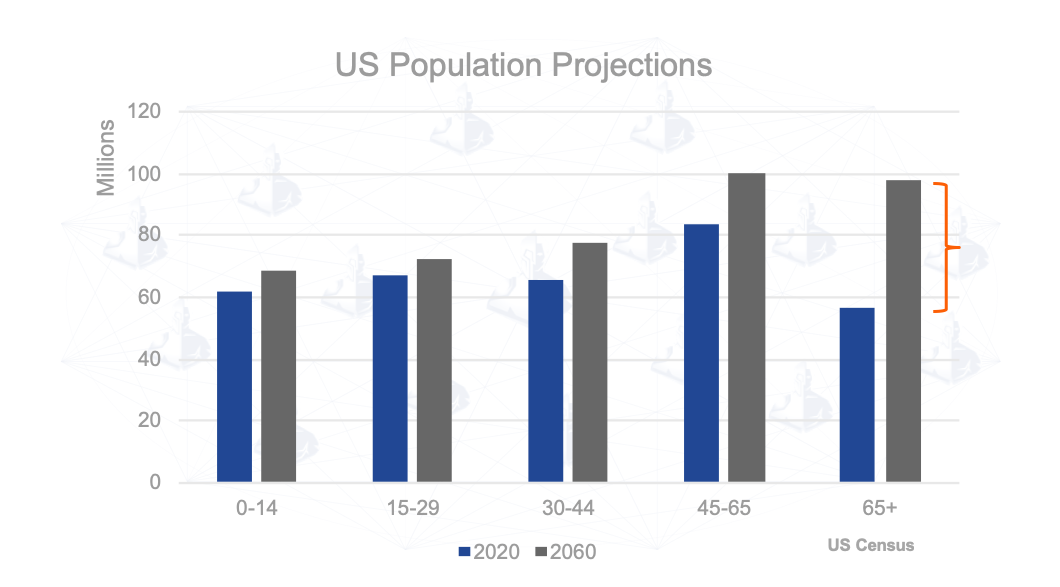

To understand this better, let’s look at the projected US population by age-group over the next 40 years — a time horizon that is within the life horizon of a majority of the population.

Key takeaways:

- The 65+ age-group (erstwhile “retired”) shows the most dramatic change – a 40 million increase to nearly 100 million – a whopping 25% of the total US population in 2060.

- Assuming 25% of the 65+ group participates in the labor force, that is a 10 million increase in labor force. The number could be higher as traditional notions of retirement are swept away by our need to live and work longer.

- US will need to employ 40 million more people in 2060 to keep unemployment at the current 4% rate – 10 million of that – 25% –comes from the longevity effect.

In short, longevity is a supply-shock to labour market, just like borderless labour.

Nowhere in human history have we had a demographic shift like this, nor unprecedented challenges arising from this – from how the older adults participate in the economy, to how we care for this population.

[Note: How the healthcare industry needs to prepare for this deluge of demand for accessible and affordable healthcare is a topic for later.]

Sharing Economy – Gig-driven, On-Demand, and Asset-lite

The common thread across AirBnB, Uber, and cloud computing services (e.g. Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure) is the idea of pooling of resources to be shared by vast number of consumers. This results in increased utilization of the underlying assets and new ways of consuming those assets.

Ride-sharing pools the asset (cars) and labour (drivers) to meet the demand; AirBnB pools assets (under-occupied homes); cloud-computing pools computers and optimizes utilization.

All these are examples of how capital and labour are being reshuffled to ease our consumption of the assets as a pay-as-you-go utility.

It is too soon to assert if this scale of asset and labour pooling will drive the demand for labour and wages.

Key questions being researched and debated include:

- Will we need less computers overall? Will we need less operators of them?

- Will we need less hotel rooms and staff?

- Will we need less drivers and cars?

Unlike borderless labour and longevity, the effects of sharing economy on labour will vary by industry.

Automation – Not the Sole Grinch

Humans have been inventing widgets to automate tasks for thousands of years – from wheels to indoor plumbing to Alexa. Should we be more worried about the effect of borderless labour, longevity, and sharing economy on jobs?

Or is the velocity of our inventions outpacing our ability to develop new competencies, resulting in keep large sections of society becoming unemployed? Is speed of automation the only new wrinkle on automation in the 21st century vs. all its predecessors?

Regardless, technology driving the globalization of labour, increasing life expectancy, and delivering higher utilization of capital and labour looks to be ominous disruptors of organized, country-specific employment as we know it.

Will that result in a jobsageddon and consequently a new societal order in the 21st century?